The following text is excerpted from “Cultivating charismatic landscapes: Designing for preservation and resilience of Texas’s natural swimming holes.” You may find the full text along with a list of research citations here: https://rc.library.uta.edu

Figure 1. Public swimming area at Blue Hole Regional Park in Wimberley, Texas (photo taken 03/14/2023 as part of an observational site visit).

Three Texas swimming holes were studied as part of this research and are highlighted above.

The swimming hole landscape is significant in that it provides an immersive interface between humans and the natural world within a riparian corridor. Distinct characteristics of local watersheds and regional ecological systems result in a unique expression of the natural environment specific to each Texas swimming hole. Notably, these environmental components, along with human culture and settlement patterns, are all interrelated, underscoring the importance of health and harmony within each.

For many generations of Texans, natural swimming holes have provided a unique opportunity for recreation and leisure during the hot summer months. Found in both urban and rural settings, the aesthetics and amenities of these community gathering places vary by location, but they are typically found along streams or near springs, providing ample opportunity for users to picnic, swim, and congregate with others. Though some have been developed and are managed by parks services and other responsible parties, others are more vernacular in nature—off the beaten path with the journey as important to the experience as reaching the destination.

Figure 2. Blue Hole Regional Park in Wimberley, Texas closed early for the season in 2022 due to low streamflow (photo taken 09/18/2022 as part of an observational site visit).

Over decades of use, and with population growth fueling urban expansion and straining watersheds and other natural resources, many of these landscapes have deteriorated, and user experience has become significantly altered. Further, climatic factors—including seasonal and often significant swings between drought and flooding—impact streamflow and overland flow, directly affecting traditional form and use of these landscapes. Will it still be possible to enjoy these unique landscapes in the future?

The purpose of this study was to better understand the cultural and environmental significance of Texas’s natural swimming holes and to determine how the field of landscape architecture may preserve the function and spirit of these places through best practices in place-specific, resilient design and recommendations for mindful management. This study focused on three guiding research questions: (1) Why is the natural swimming hole environment important culturally? (2) What factors contribute to the deterioration of natural swimming holes and/or negatively impact usage? and (3) How can the field of landscape architecture ensure natural swimming holes remain environmentally resilient and accessible for future generations of Texans?

Figure 3. The following flow chart summarizes the research methodology.

Over the course of a year-and-a-half, the research materialized: a literature review was conducted, case studies were reviewed, swimming hole users were surveyed, experts were interviewed, and three sites were visited throughout various seasons to collect observational data. The data collected was classified into a matrix and further analyzed and synthesized, resulting in nine design and management guidelines specific to the Texas swimming hole landscape. These guidelines highlighted the importance of promoting regional context and values, inclusive programming and storytelling accessibility, enhancement and restoration of riparian ecological systems, and overall watershed health as important design considerations for the Texas swimming hole landscape. Recommendations for public education at local/community and regional/state decision maker levels were also deduced.

After an application exercise which tested the nine guidelines through a design and management proposal for a study site in Glen Rose, Texas, the following conclusions were realized:

Why is the natural swimming hole environment important culturally?

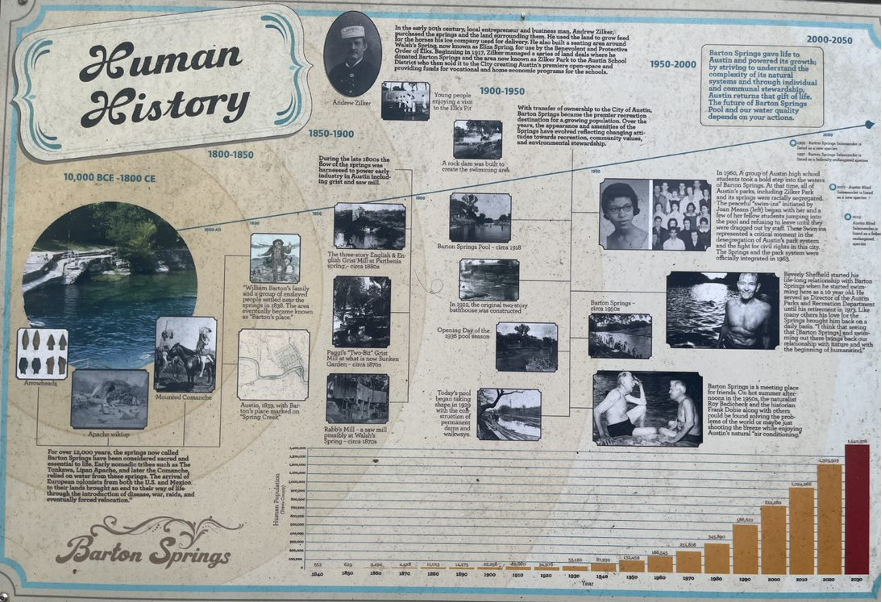

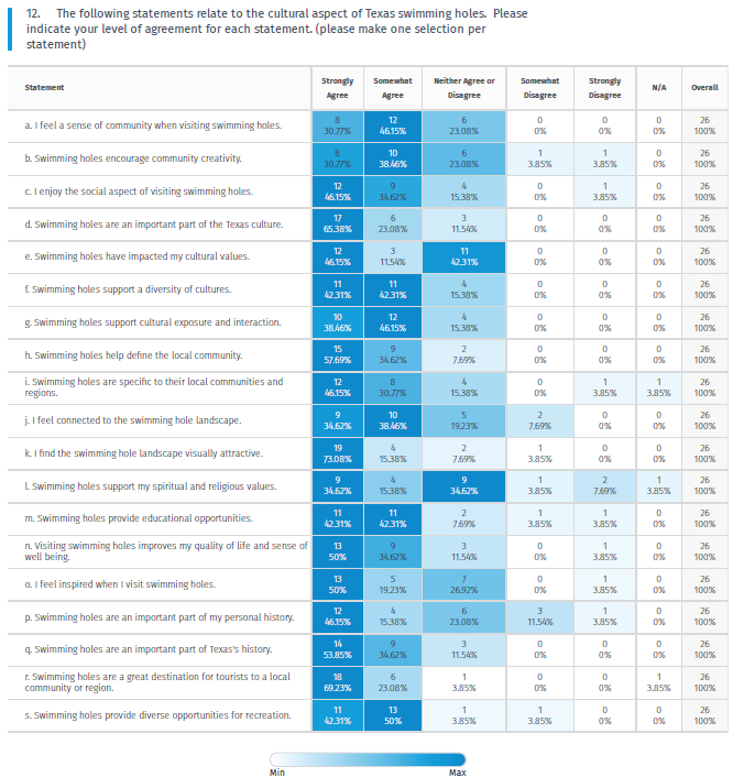

Humans have a reciprocal relationship with the natural environment (Jiang and Marggraf, 2021). These landscapes contribute to our identity, often manifesting in our built environment and societal norms (Daniel et al., 2012; Jiang & Marggraf, 2021). Users identify with multiple cultural values derived from the natural swimming hole landscape, including a sense of community, Texas culture, and visual attraction to this type of landscape (see user survey responses, Figure 6).

Natural swimming holes were influential on historic settlement patterns in Texas, both serving as an economic and cultural center and influencing the location and layout of our communities (McKinney, 2023; Duggan, 2023). These landscapes are documented as important to Texas’s cultural heritage through historical markers, photographs, books, and modern-day user interfaces such as social media. Natural swimming hole landscapes are unique in that they engage users with the outdoors in a one-of-a-kind, regionally specific riparian environment through recreational opportunities and space to congregate with others.

What factors contribute to the deterioration of natural swimming holes and/or negatively impact usage?

Both watershed management and urban development practices impact streamflow and water pollution. We have lost half of the big springs that existed in Texas due to water withdrawal (McKinney, 2023). In one reaction to the negative impacts of urban development, the Save Our Springs coalition was formed by local community members in response to the degradation of water quality due to developers building in the recharge zone for Barton Springs (McComb, 2008; Branch, 2023). Climate change and swings in precipitation impact streamflow as well, and designers should consider alternate activities to swimming as part of the design for these landscapes (McKinney, 2023). Finally, these landscapes are being “loved to death,” and this overuse compromises the local ecological resiliency and negatively impacts user experience (Duggan, 2023; McKinney, 2023).

How can the field of landscape architecture ensure natural swimming holes remain environmentally resilient and accessible for future generations of Texans?

This study’s resulting design guidelines provide a roadmap when designing and planning for resiliency of the natural Texas swimming hole landscape. Considerations include promoting regional context and values, promoting inclusive programming and storytelling accessibility, enhancing and restoring riparian ecological systems, and promoting overall watershed health. Public education in resilience design and planning at both the local community level and the regional/state decisionmaker levels is crucial in ensuring these landscapes are preserved for future generations of Texans.

Figure 10. Application of the design guidelines to the study site in Glen Rose, Texas.

This study examined opportunities for resilient design and management of the natural swimming hole landscape from three distinct levels: self, community, and region. Looking first at the individual user, future research opportunities include an assessment of how the cultural values associated with the natural swimming hole landscape might be made applicable to other types of landscapes. Community-level research would include the logistics of making water-wise technology accessible to users. A study of effective educational initiatives implemented at the community level to teach resiliency practices in our homes and local schools could promote these standards as part of our common knowledge and daily routines. At the regional watershed level, opportunities exist to investigate the implementation of detailed regional watershed planning strategies that incorporate a large-scale green infrastructure network for the entire watershed. An investigation into “closing the cycle” on water usage at the watershed level would also positively impact the swimming hole landscape. Finally, testing the design and management guidelines ascertained through this study by way of implementing informed designs in the field at a variety of swimming hole locations would likely result in the identification of additional related topics for future research.

Figure 11. Users explore the creek bed downstream from the swimming hole at Glen Rose, Texas (September 2022).

The field of landscape architecture is in the business of engaging people with the outdoors (Duggan, 2023). In Texas, the same experiential deterrents impacting natural swimming holes are affecting other landscapes as well. The effects of climatic shifts and watershed management practices will influence our design and planning processes to a greater extent in the future as urban expansion and population growth continue straining our natural resources. Landscape architects should also consider swimming hole health as an indicator for overall watershed health due to the location of swimming holes within the drainage basin. This could help the profession assess environmental needs and ultimately design for a larger impact if this emerging body of research is applied in a more holistic way. Finally, the resiliency guidelines recommended for this culturally significant landscape should be made applicable to other types of landscape design in an effort to promote cultural connection and deeper user fulfillment.

Figure 12. Enjoying time with a childhood friend at a popular private swimming hole outside of Lockhart, Texas (Summer 1994).

Figure 13. Various Texas swimming holes. Images: Creative Commons flickr.com

The genesis of this study topic evolved through an exploration of culturally significant landscapes throughout the state of Texas, specifically those which promote community building and encourage interaction between humans and their natural environment. Swimming holes quickly moved to the top of the list, as I have many fond memories of enjoying these landscapes with friends and family during my childhood years in South and Central Texas. Spending time in recreation and leisure within these riparian corridors has also influenced my understanding and appreciation of the environmental significance of these landscapes. My individual journey during this study has been incredibly rewarding, as personal experiences fused with Texas tradition and environmental determinants on the canvas of regional riparian landscapes and local lore.

Find more information here: www.swimmingholes.org