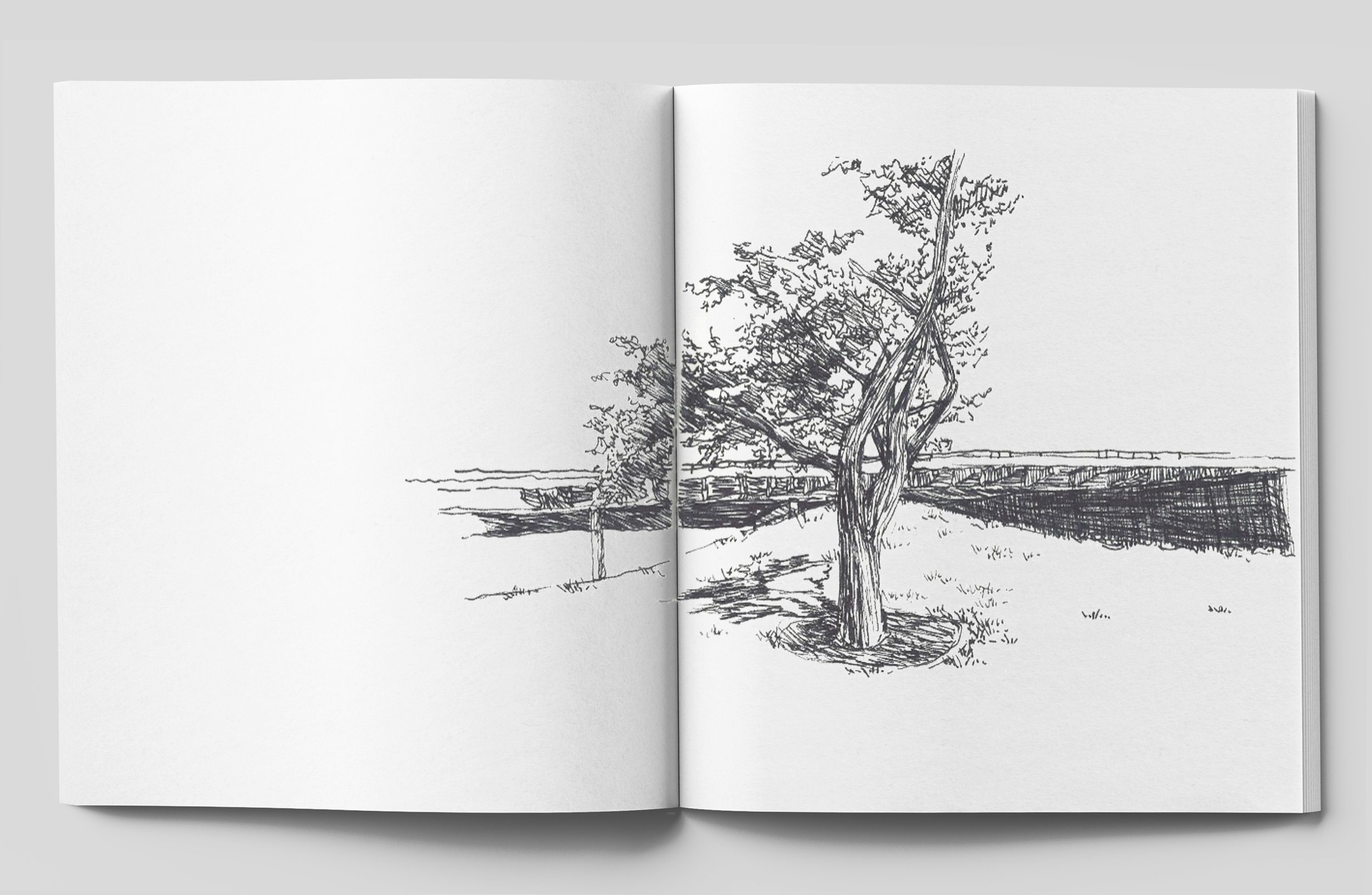

“A transplant to both Texas and Dallas, long walks downtown and in its surrounding neighborhoods have been my favorite medium to become more familiar with my new home.”

Studio Outside’s Meghan Obernberger moved to Dallas in June 2022. Since then, she has sought to explore the city by walking, often without a destination in mind, but always recording her experiences in her sketchbook.

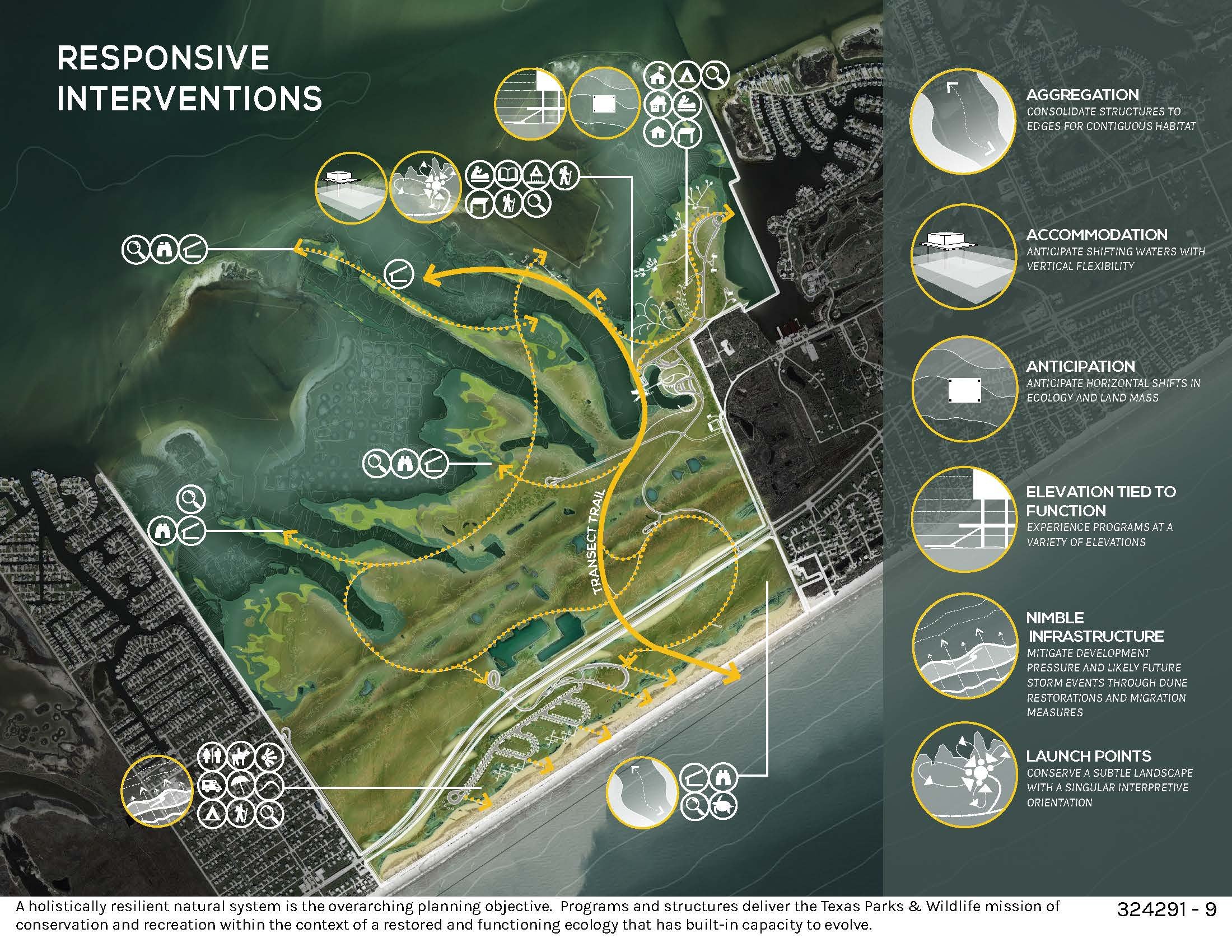

A JOURNEY BEGINS

“Coming to Dallas, I was warned about the car-centric scale and planning of the city. While this reputation is fair, I have been pleasantly surprised by the walkability and public parks within Downtown Dallas.”

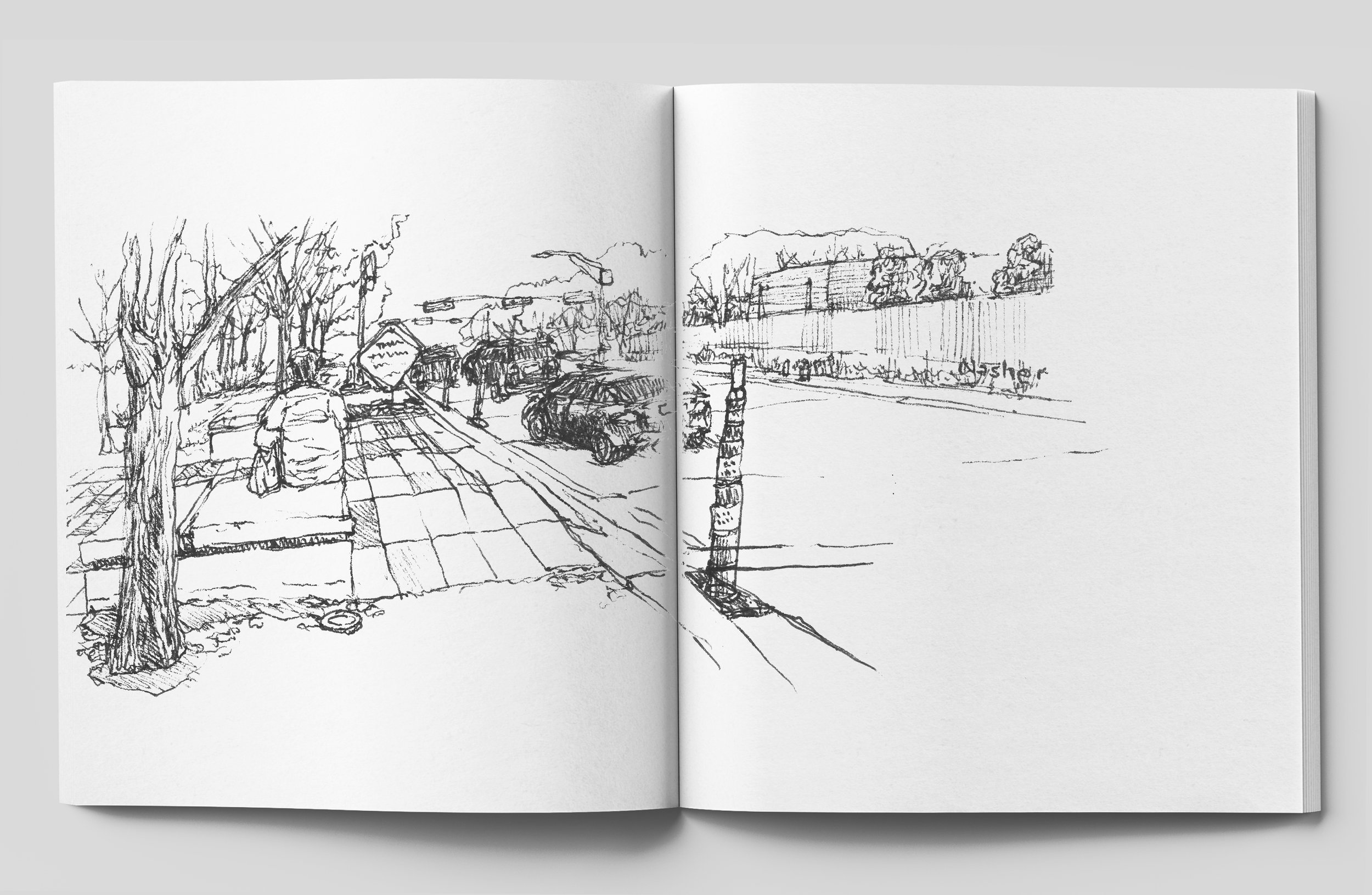

As she sets off from her home, Meghan finds plenty of infrastructure in place for the pedestrian. Sidewalks line the roads, and pedestrian crossings are aplenty. Oak and sweetgum trees provide some much-needed shade along several streets, while dandelions cropping up through sidewalk cracks delights the eye. This should feel like a promising start to a journey, yet she quickly recognizes a potential problem - even the presence of this infrastructure is not enough to encourage a culture of walking, and Meghan often finds herself the sole pedestrian.

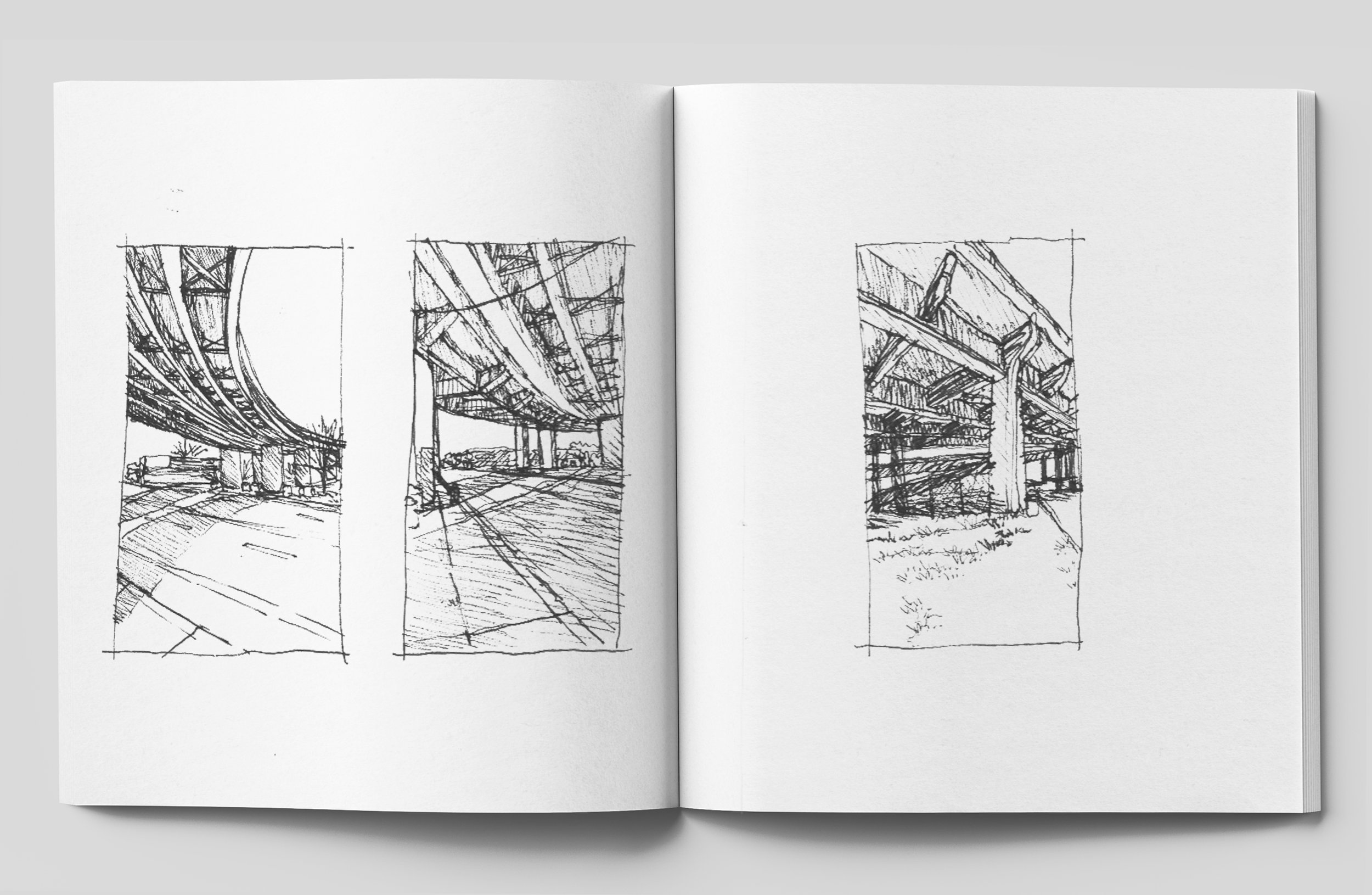

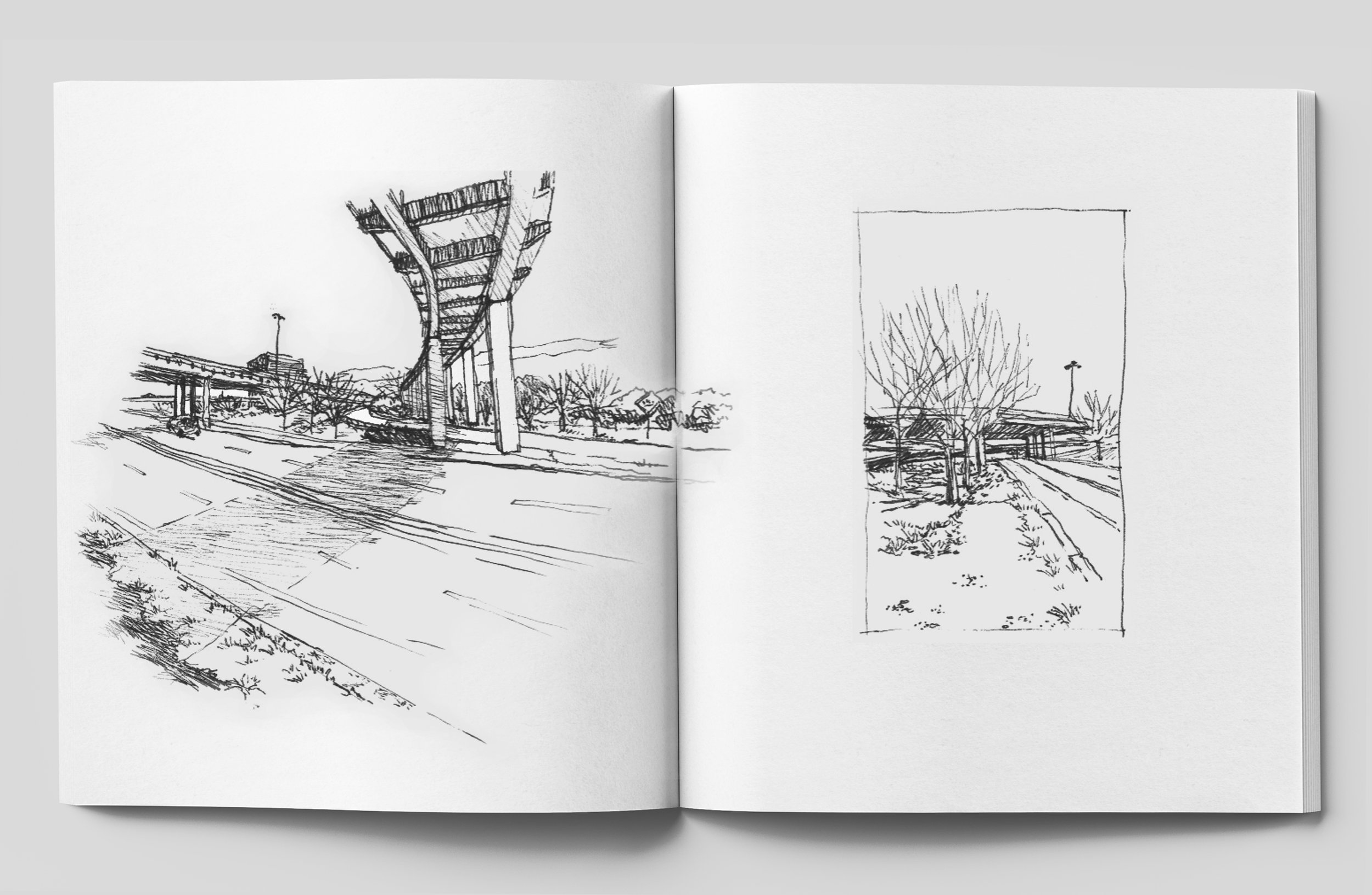

ENCOUNTERING OBSTACLES

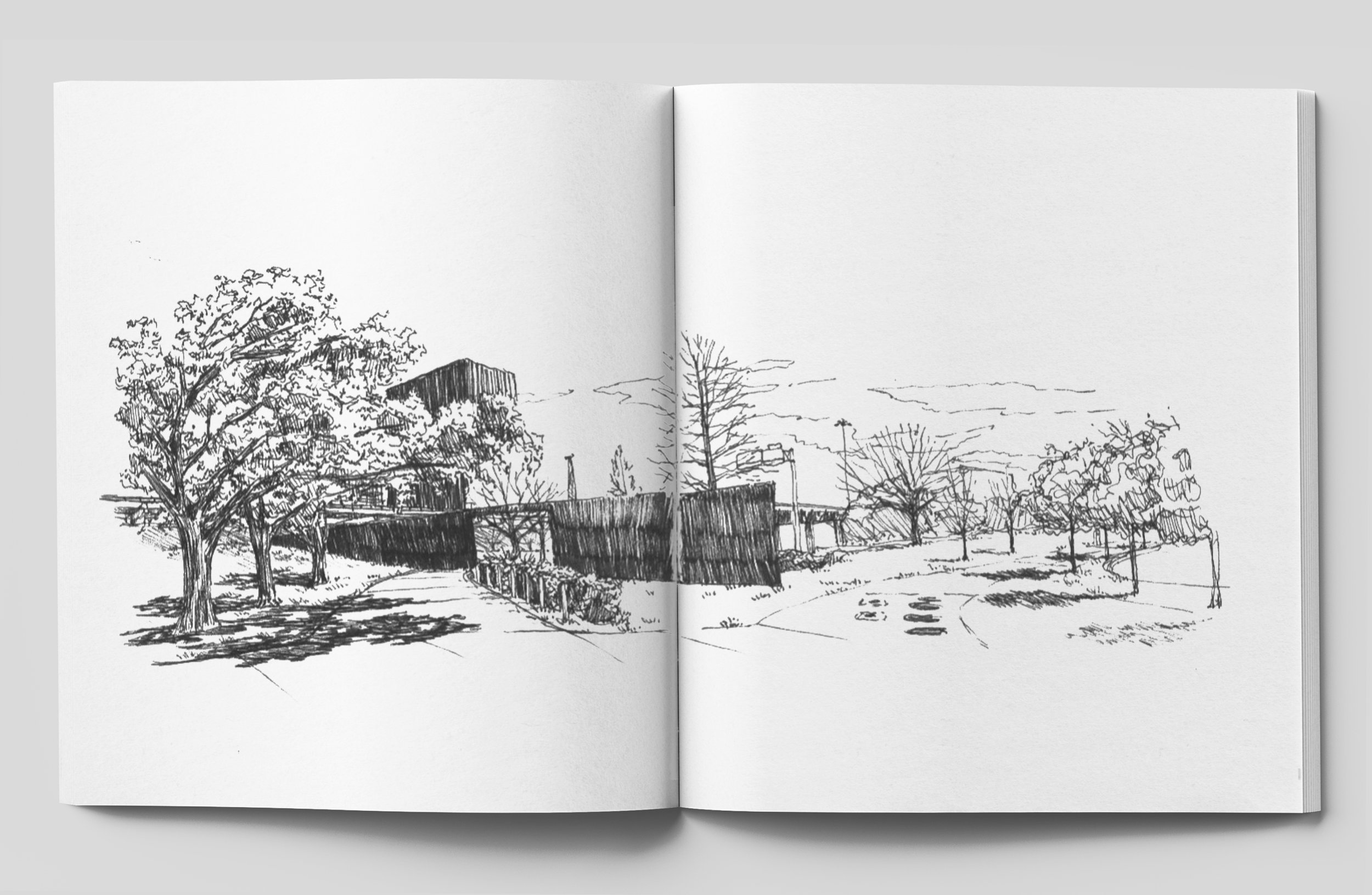

“These spaces can still feel like a psychological and physical threshold – not to be crossed and preventing further connections both within and outside of Dallas’s downtown.”

To go downtown, Meghan must walk through a series of freeways and highways, with bridges streaking overhead, their imposing presence hard to ignore. Underneath them, the DART light rail track winds through the street traffic. The sidewalks here can feel like an afterthought – they are often broken, obstructed, or simply absent, making the whole experience intimidating and distinctly uninviting.

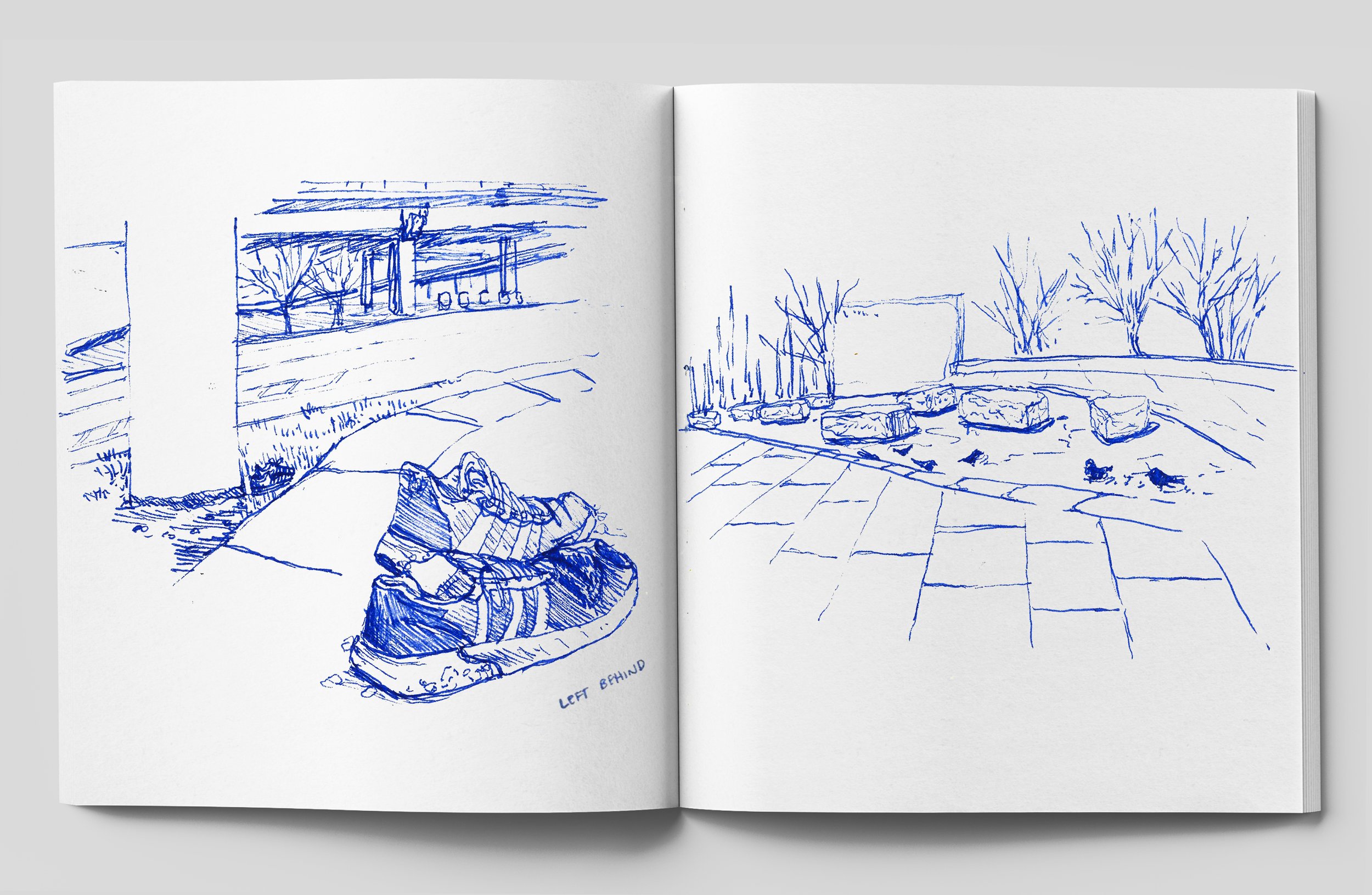

DISCOVERING RESPITE

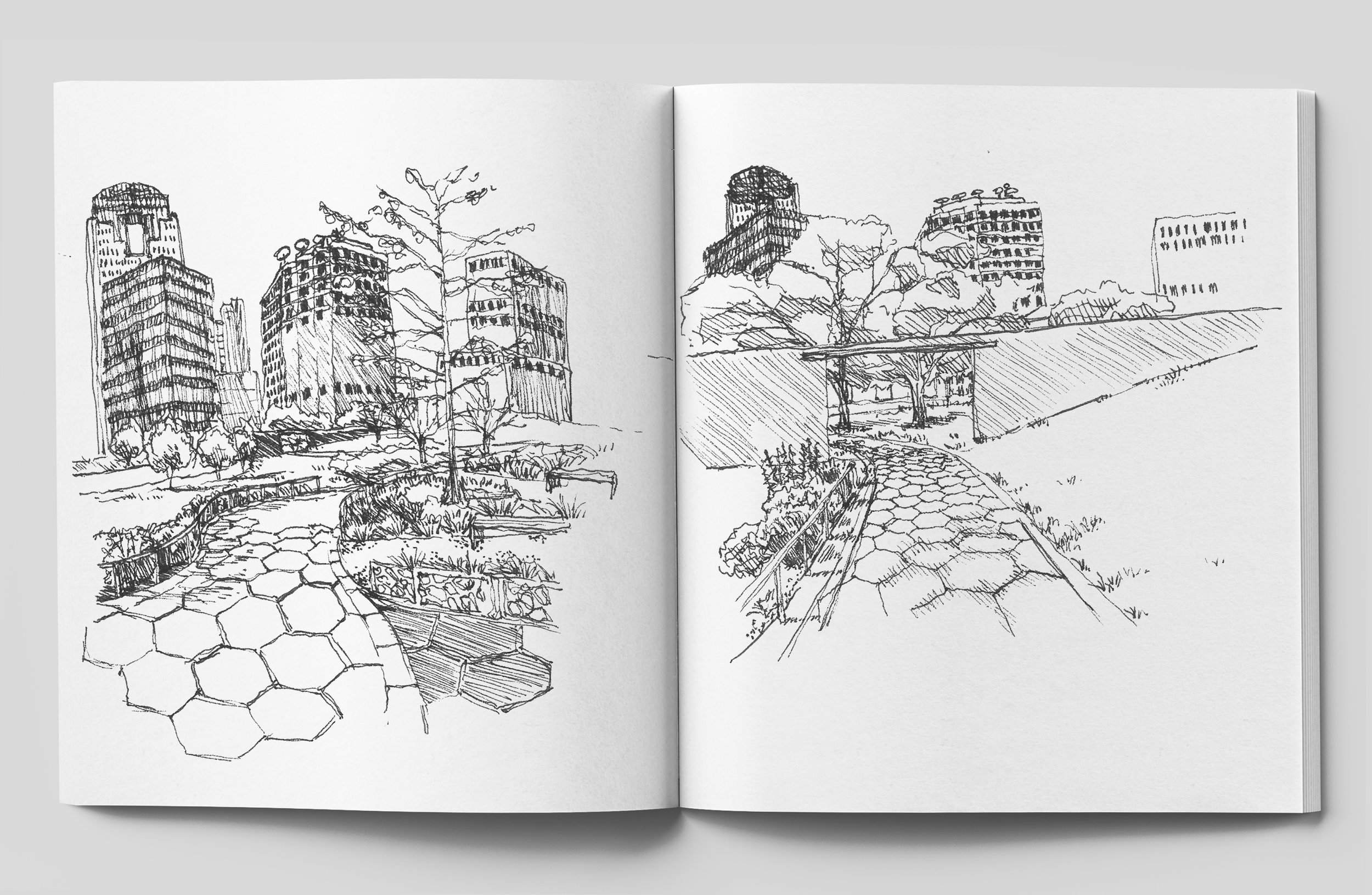

“The parks and public areas directly interface with Dallas’s freeway system – each taking a unique approach to activating an otherwise hostile space for pedestrians.”

Despite the streetscape's overlooked condition, Meghan finds moments of relief in the form of parks and public spaces scattered throughout downtown. These spaces break up the monotony of the railroad bridge complex, providing an escape from the concrete jungle. The carefully designed parks revitalize the public areas, a stark contrast to the undeniable air of neglect felt when walking underneath the I-75.

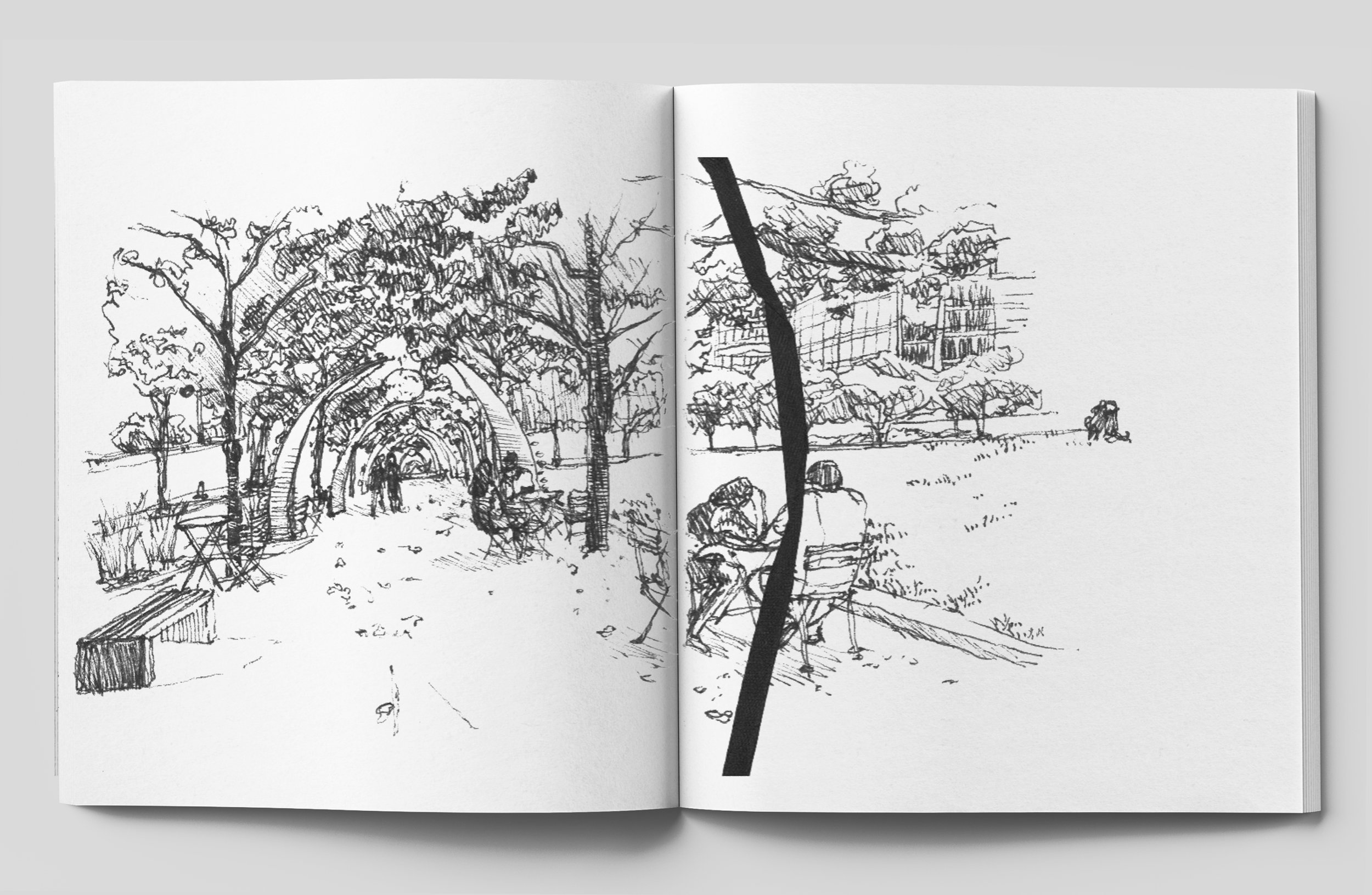

The first of many such spaces is Carpenter Park. Once she’s traversed the crossing underneath I-75, Meghan finds herself drawn into an oasis of trees and fountains. Carpenter Park- with its earthwork punctuating the highway, provides a welcoming atmosphere compared to its imposing surroundings. No longer uncertain or apprehensive, Meghan continues her walk beyond this park, newly invigorated.

INTERLUDE

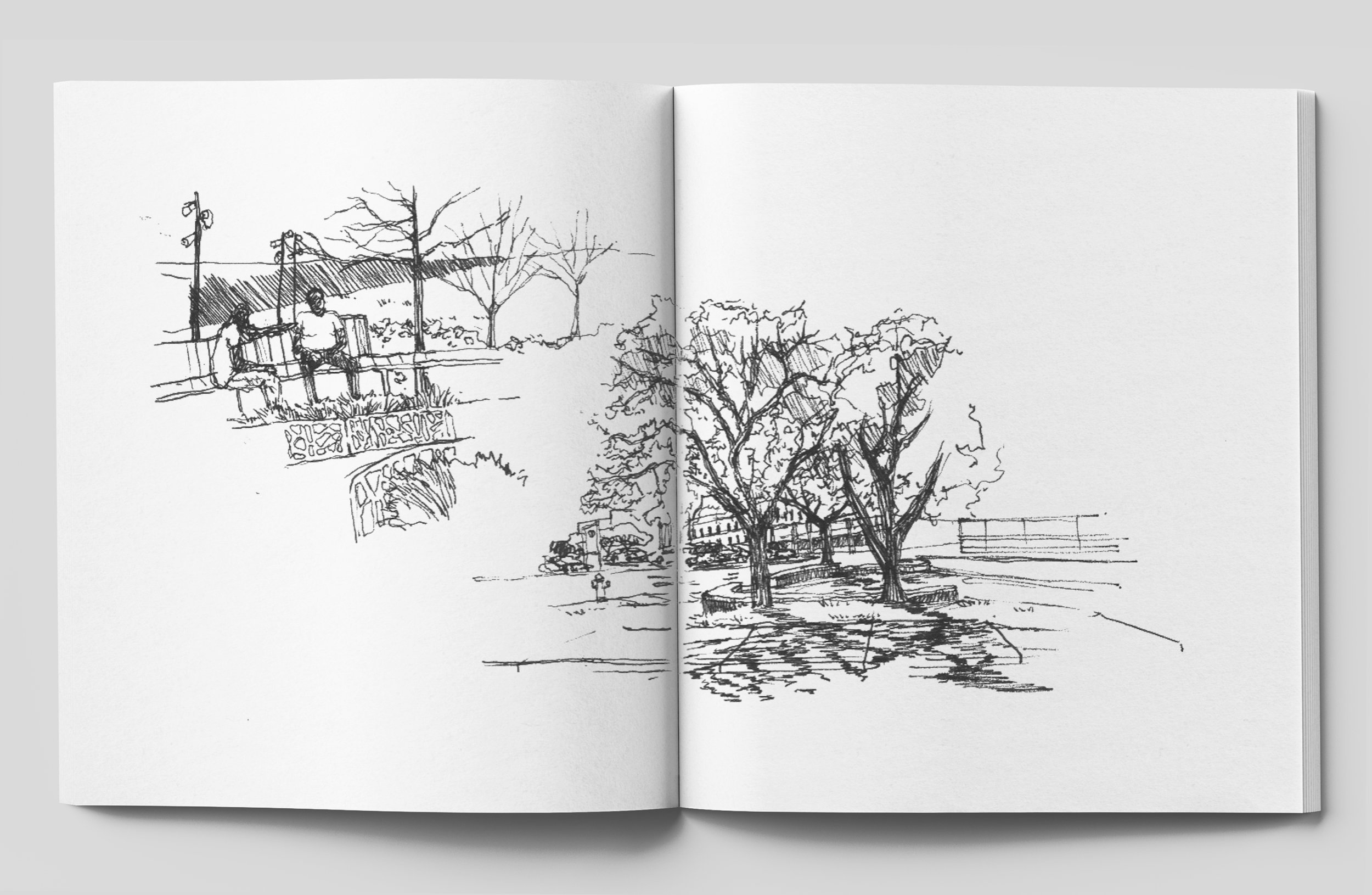

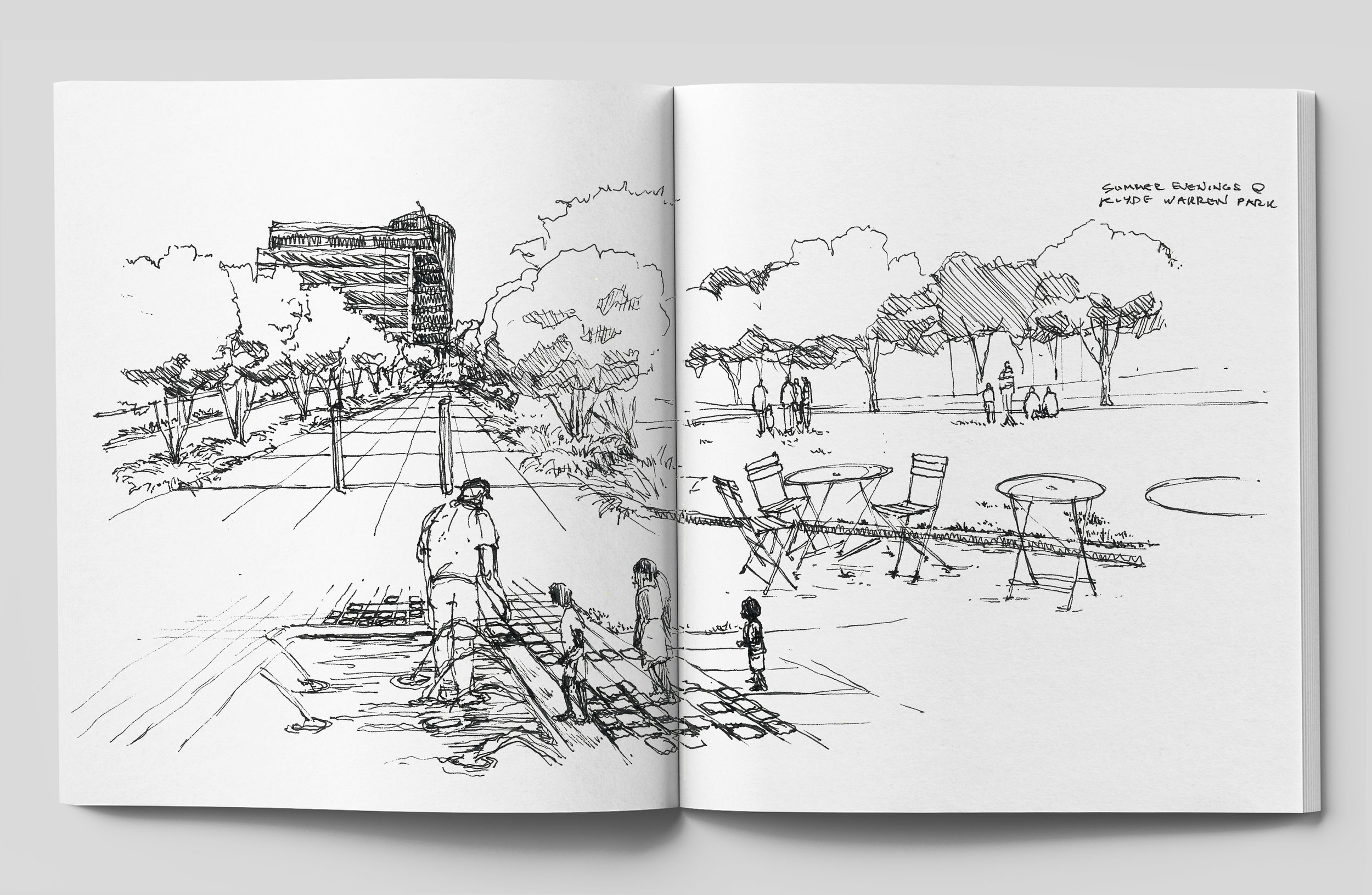

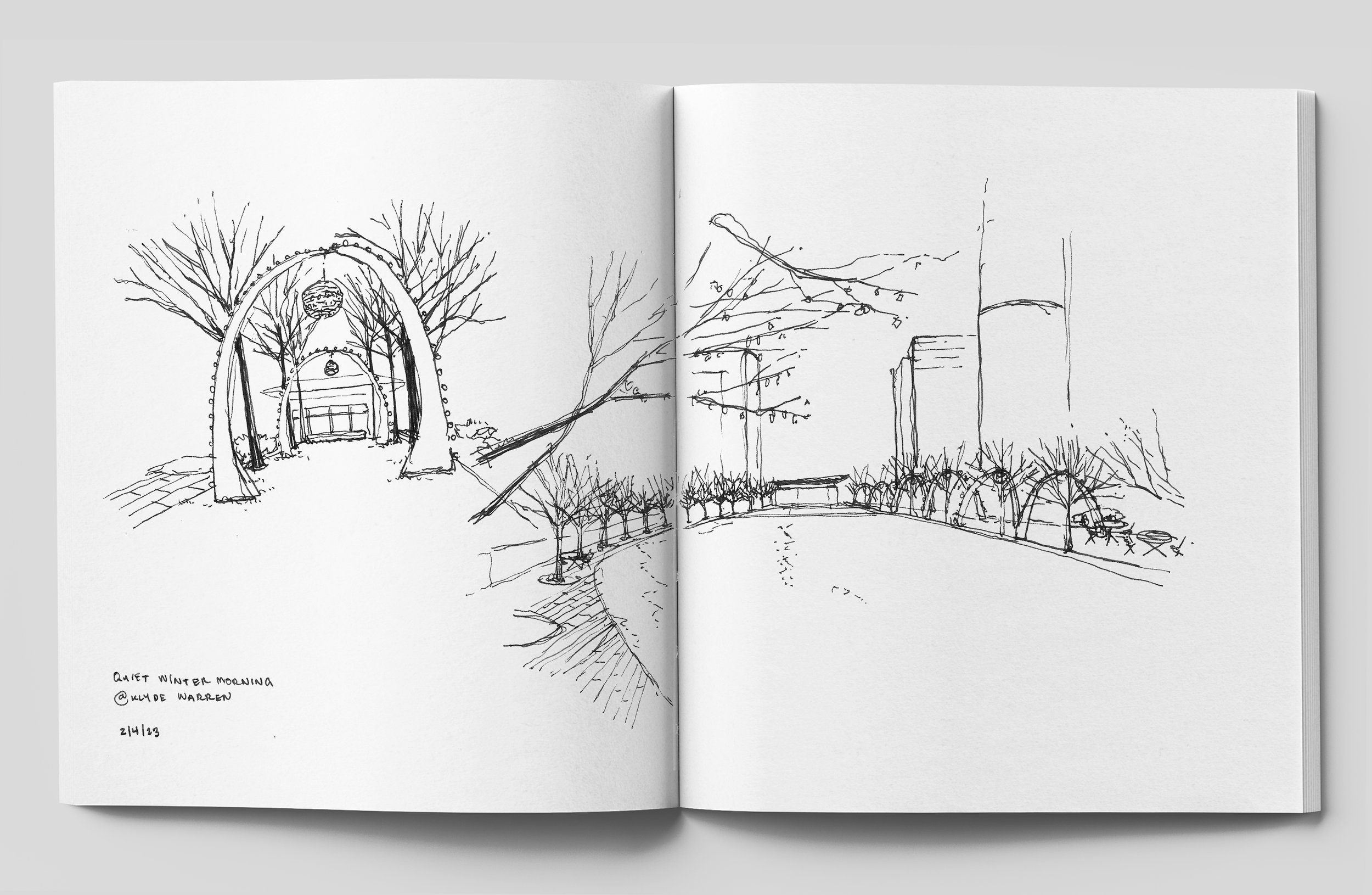

“It can be hard to get a moment alone in this park. Even in the early morning hours, a team of custodians scours the grounds.”

In Klyde Warren Park, there is an immediate sense of arrival. Food trucks line the perimeter of the park, and markets pop up all around. The air is filled with shrieks of delight from children as they play in the fountains, and the lawn invites park-goers in. The commotion of activity in the park drowns out the highway, making visitors completely forget it. Klyde Warren Park often makes itself a destination in Meghan’s journey.

GOING THE DISTANCE

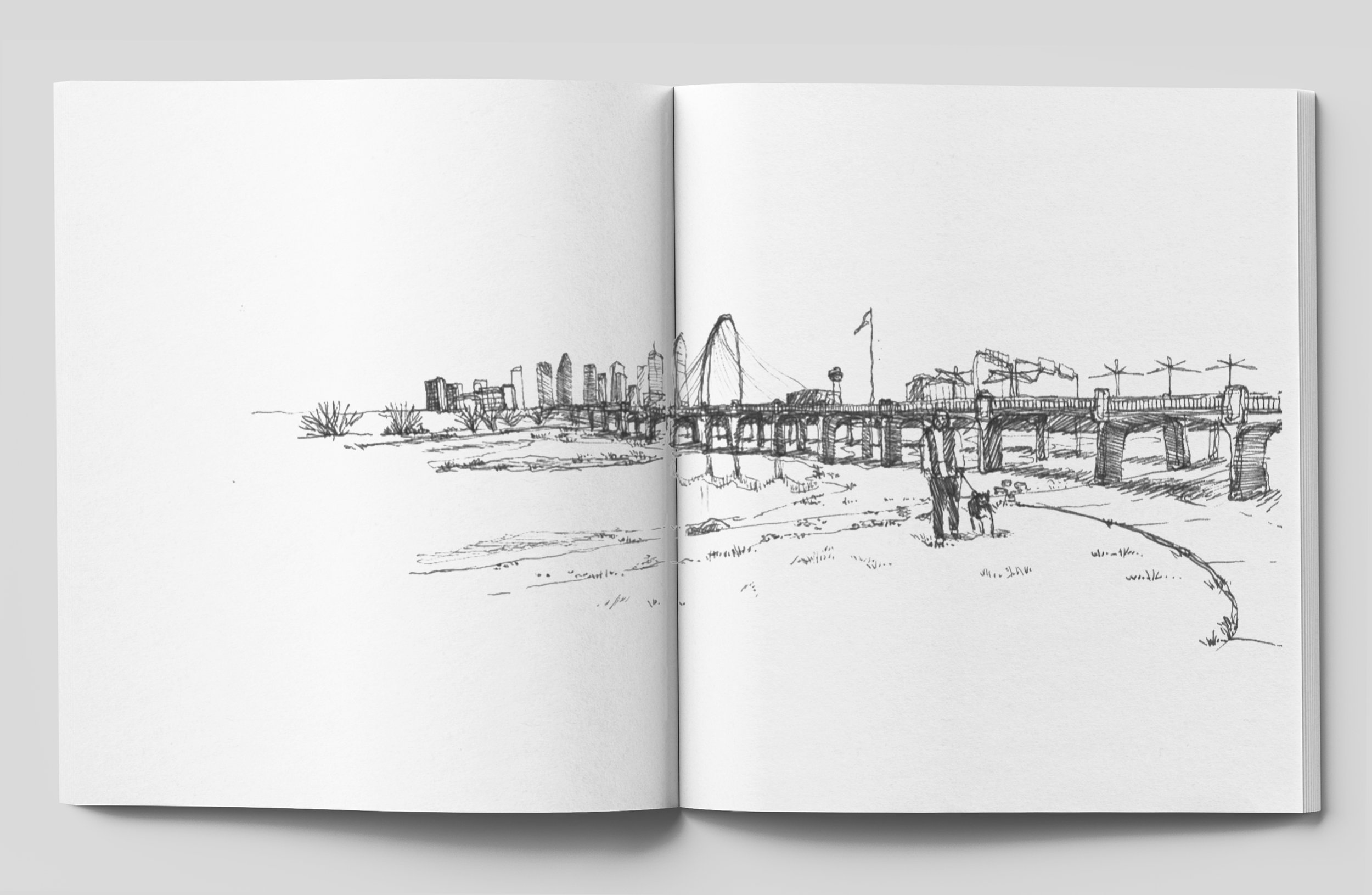

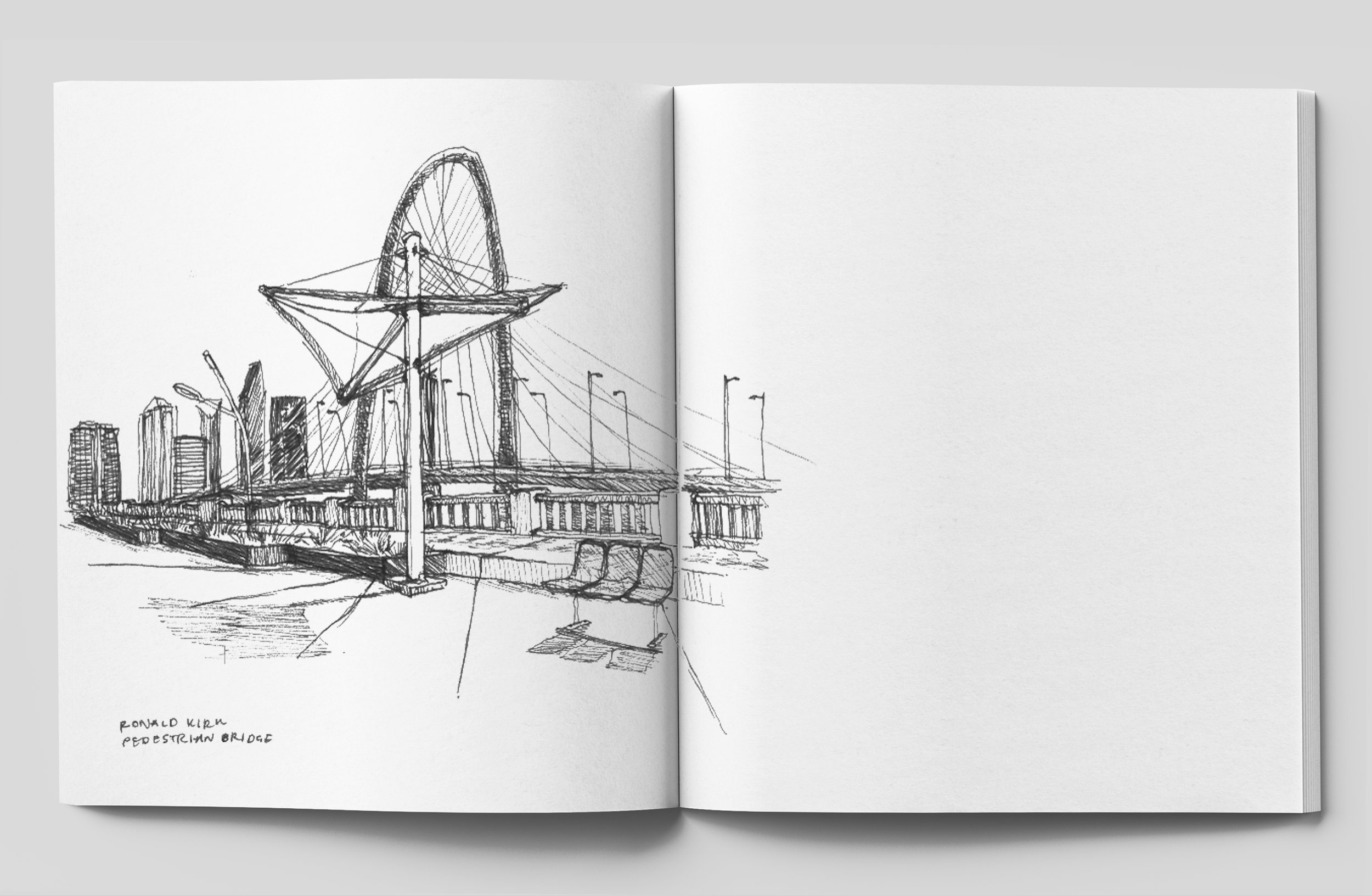

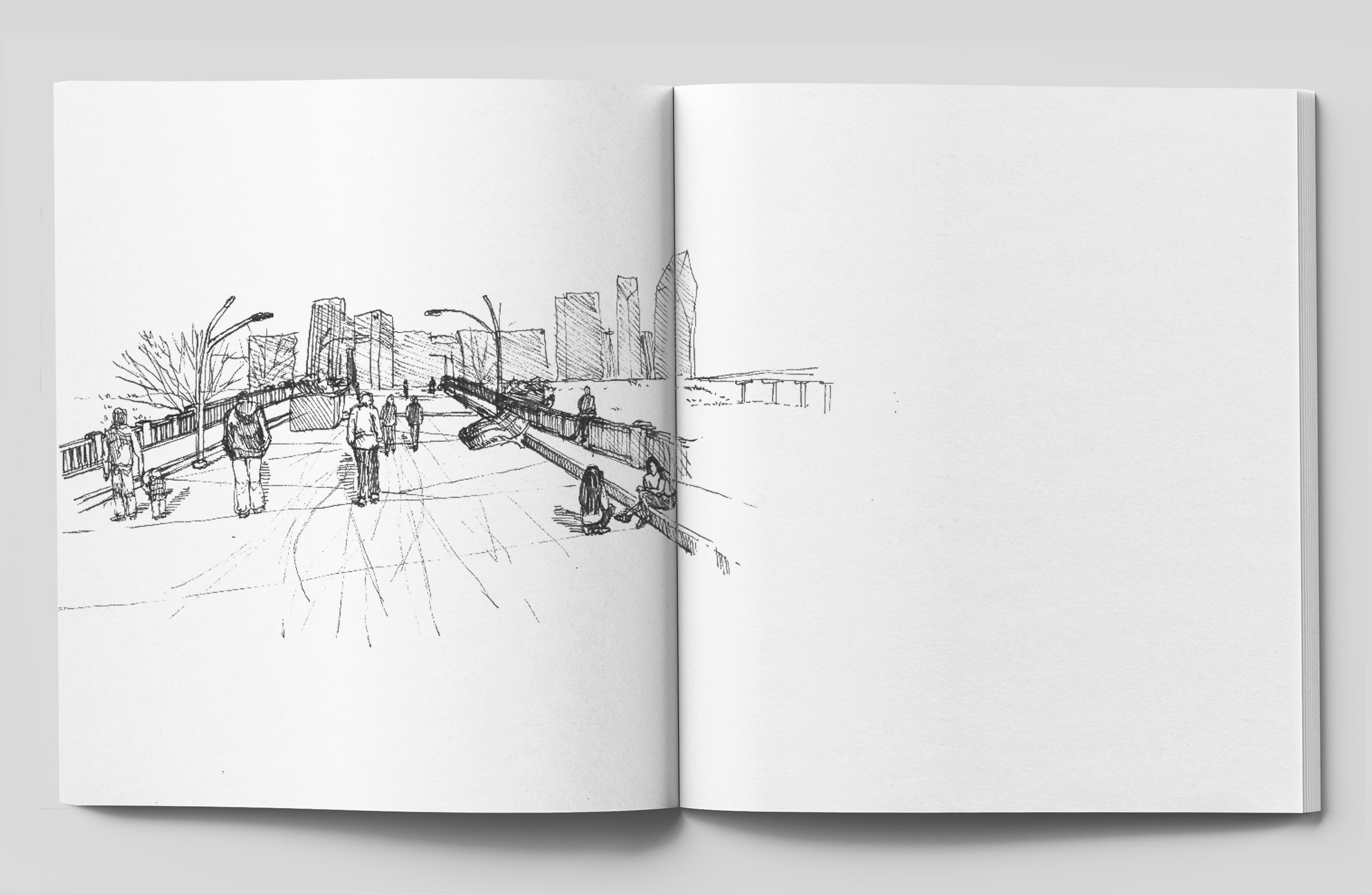

“The sprawling view of the Dallas skyline, expansive Trinity floodway, and towering Margaret Hunt Hill bridge adjacent provide a natural attraction at the site through all hours of the day.”

As she rambles beyond downtown, Meghan finds a space that parallels the highway. On the Ronald Kirk Bridge, the adaptive reuse of a former freeway is evident. Meghan admits that the bridge is hard to access as a pedestrian but still finds that the canopies and the skyline attract plenty of people. Once there, the linear structure, the moving traffic, and the shifting views create a public place that invites her to stay and to keep moving forward – a perfect culmination of what a pedestrian experience should be.

Meghan’s Downtown Walks