part I.

“...new conceptions of landscape beauty can be convulsive, disturbing, and challenging; through them we confront the entanglement of personal consumption, waste and the postindustrial site.”

The dock at Pelican Point is enveloped by a forested wetland. Twenty years ago, this would all have been open water.

White Rock Lake is breathtaking in the fall. Hues of red, yellow, and green stand out, vibrant against an overcast sky and reflecting in the lake’s still waters at Pelican Point. It is late in the afternoon as I walk along the edge of the lake and stumble upon a dock, hidden amidst a tangle of branches and shrubs. I walk through the thicket and emerge at the landing to find a panoramic view of the lake, framed by a patch of bull rush around the dock.

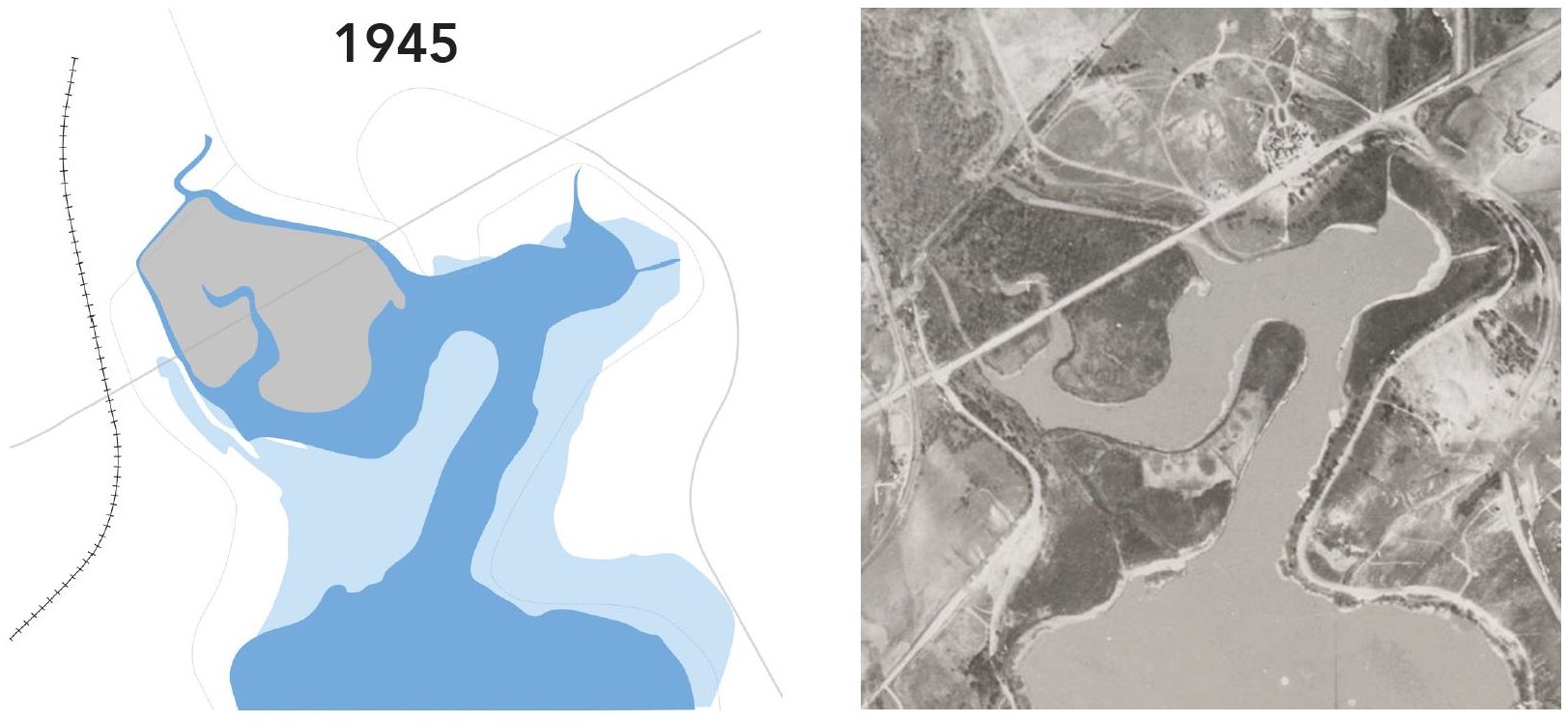

As I sit out here, watching the lake and savoring the stillness of it all, it’s hard to imagine the view as anything other than it is now. But twenty years ago, this spot would have been an entirely different landscape; the dock would have extended invitingly over the water from a grassy, unobstructed shoreline, offering vistas of the lake at every step along its length.

How quickly the shoreline has changed! Even now, I see mud swirling so close to the water’s surface. It is the natural course of every lake, constructed or otherwise, to silt up, turn to marshland and eventually become forested land. This process is particularly accelerated in urban lakes - it is not a stretch to imagine that in another twenty years, even the dock’s landing could be completely enveloped by forested wetlands. Watching the pelicans huddled together over branches in the water, I wonder if they will still be here when tree canopies blanket the open skies above them.

My gaze shifts from the pod of pelicans, tracking the coots as they wade through the water, pausing on the delta where the Reinhart branch meets the lake, before settling on something that looks like it doesn’t belong - an upturned shopping cart! Only a part of it is visible above the water’s edge; it will undoubtedly reveal itself fully during hot summers and periods of drought, when the water recedes, and Pelican’s Point is nothing but a muddy beach.

Idly, I wonder what else can be seen when the beach surfaces. Vast expanses of exposed mud and debris still provide a home for the birds of Pelican Point, but an irrefutably polluted lake is hardly the picture of a healthy urban oasis. Styrofoam cups, plastic wrappers, metal cans – a potpourri of human and industrial waste makes itself visible and forces us to reckon with the pollution to which we have knowingly or unknowingly contributed.

Oils and chemicals sit undissolved in the forested wetlands.

It is moments like this when we confront our relationship with the lake, and through this confrontation practices such as the volunteer-led Shoreline Spruce Up are born. People that are a part of the White Rock Lake community claim the landscape as their own, doing their best to keep the changing shorelines free from debris.

I’m thinking about a swirl of rainbows shimmering on the surface of the water in the thicket behind me, some insoluble chemicals that will quickly be smothered by yellowed leaves and become another layer of nutrient-rich debris in the shrinking lake. Even the most thorough clean-up couldn’t possibly keep up with the rate at which the wetlands are growing. Pelican Point is at a crossroads, and to keep it from becoming a trash-strewn floodplain forest, a bigger restoration effort - dredging - needs to be called to action.

part II.

“We need acts of restoration, not only for polluted waters and degraded lands, but also for our relationship to the world.”

In this moment, Pelican’s Point is all mine. No other person has ventured out onto the hidden dock, and I sit in complete silence except for the occasional bird call. It is the perfect setting to contemplate the lake; in preparation for my afternoon on the dock, I have pored over the city’s White Rock Lake Dredging Feasibility Study report from 2020 and think about what I have learned.

Our current predicament of a shrinking lake in need of dredging is one that the lake-adjacent community has faced many times over, ever since White Rock Park was established in 1929. As early as 1937, the people of Dallas and city officials agreed that the lake was simply too shallow to swim, fish or sail in, and dredging was soon underway. The lake has been dredged three more times. With every dredge, the lake’s hydrologic processes were altered, reshaping the lake’s landscape. Our last blog post describes this dance between the two.

The feasibility study also notes that although the lake has been dredged every twenty years or so, this is not nearly frequent enough with how fast the lake is silting. Dredging as a management practice is expensive. A single dredge would cost over a hundred and fifty million dollars. Furthermore, dredging is complex. Even if the funds were to be acquired, the city would need permits and assessments from so many different governing bodies, including the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

It is little to no surprise then that today, three years from when the study was done, dredging remains to be seen at White Rock Lake. I find this somewhat relieving – well as I know how important it is to restore the lake, dredging can be a destructive act, consuming more than just silt and debris. Both the possibility of a landscape that is dredged, and that of a landscape left un-dredged loom over this fleeting display of birds and fall color.

An American Coot forages in the grass just a few feet away.

A sudden movement in the grass startles me. Between the blades of the bull rush, I see an American coot just a few feet away, examining the matted grass around it, completely unbothered by my presence. It occurs to me that I had it all wrong, Pelican Point was not all mine after all. I had been sharing it with the birds – or rather, they had been sharing it with me.

Bald cypress knees in the lawn, far from the edge of the water today.

What else have I not been paying attention to? I look more carefully at the plants around me. I see giant ragweed, bald cypress, and American sycamores - these are some of the first plants to establish themselves in wetlands. Squirrels skirt around their branches and roots, searching for food. Already a new habitat is here. In the distance, pelicans huddle together and the occasional heron perches on a log. I know from Florence Conway Houston’s Biological Survey of White Rock Lake in 1942 that these birds weren’t here then. Back in the lawn in White Rock Park, far from the edge of the water, the bald cypress trees sport knees in concentric rings around their trunks. These trees undoubtedly sat in (or very close to) water once. Everywhere I look, every moment of beauty is rooted in how the lake has changed.

Pelican Point in 2020, a muddy beach beneath the water will emerge later in the year. (this photo is by Declan Devine)

Changes in an ecosystem happen on a time scale that is different from hours and minutes so we may not always perceive them – but they are always there. The lake is always in flux. The life of the lake begins and ends with every dredge - what a delight it is to be able to perceive these changes on a time scale we can comprehend! When we learn to cherish the transient stages of the lake before the next dredge, we open ourselves up to a whole new aesthetic – we can learn to appreciate the young stems of trees as the forest they will become and the murky waters that tell us of a muddy summer beach to come. Our entanglement with this ephemeral landscape can change our relationship not only with the lake, but with the world itself.